Journey on the Trans-Siberian: Yekaterinburg

This is the third part in a series about my journey across Russia on the Trans-Siberian railway, from St Petersburg to Vladivostok, in the summer of 2018. This part covers my short but eventful stay in Yekaterinburg.

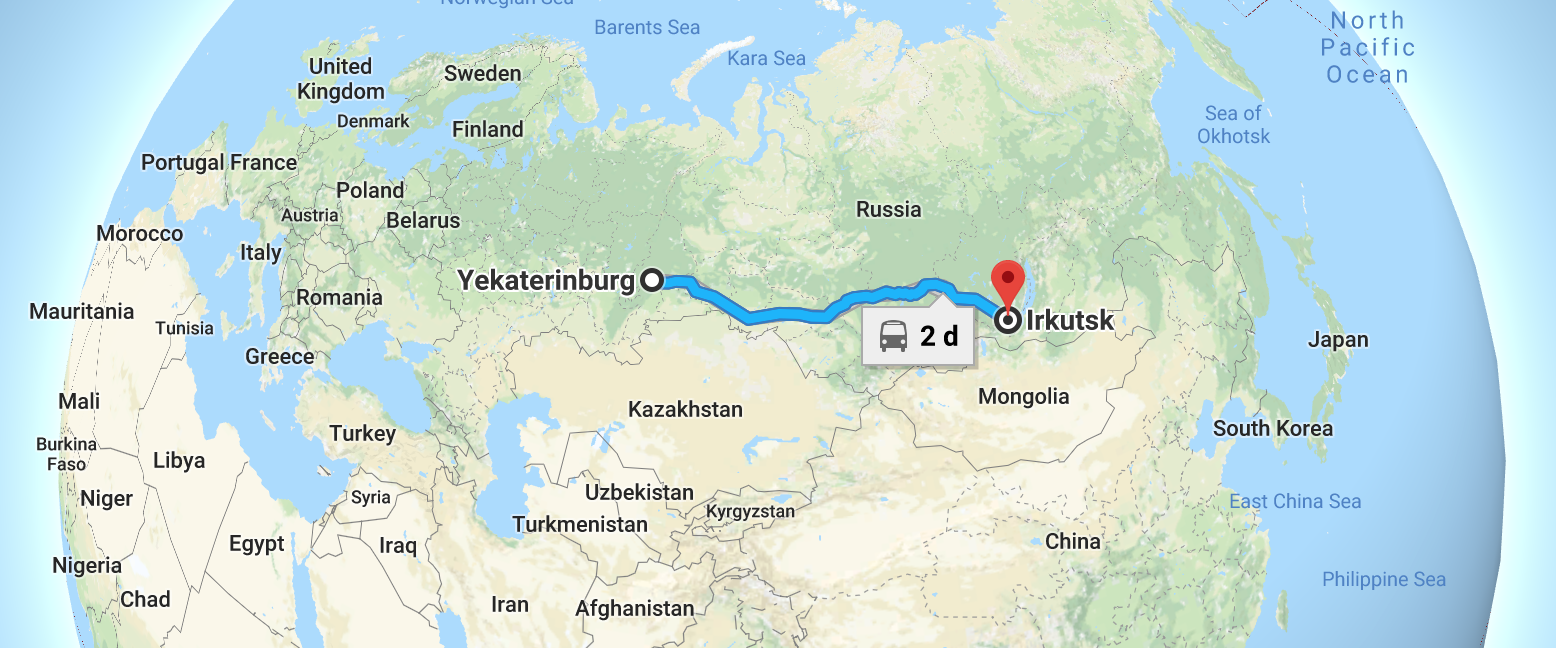

My travel route from Yekaterinburg to Irkutsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

My travel route from Yekaterinburg to Irkutsk on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Bridge

Traveling with a smartphone is easy. If you’re ever in the slightest doubt about which direction to go, a live map with your position is a tap away. No more wandering, wondering, or feeling a sense of accomplishment when you reach your destination at last. Of course you reached it, you have Google Maps!

It was with this confidence that I stepped off the Tran-Siberian train in Yekaterinburg, after a 27-hour ride from Moscow.

After punching in my hostel’s address into Google Maps, I strode out of the station and onto a wide expressway lined with drab concrete buildings and carrying muddy Soviet-era busses, and turned west in the early daylight.

One kilometer later I turned off the expressway and onto a small residential street. I continued following the phone’s instructions even as the streets turned into winding alleys, then driveways, then overgrown footpaths past children’s playgrounds that should’ve been decommissioned decades ago. To my left appeared a railway ditch, with my hostel somewhere on the other side.

As I approached the crossing per my phone’s instructions, there was no crossing in sight. So I kept going straight, past some fence and idle security guard. After a few minutes of wandering around this… Base?… I turned back.

This time the security guard, recognizing his error in letting a non-uniformed stranger stroll past him, asked me with a tinge of nervousness: “Do… You work here?”

— “No, I’m looking for a bridge.”

— “A bridge?”

— “Yes, my phone says there’s a bridge here, to cross the tracks.”

— “Never seen one.”

At that moment I noticed another man, wearing a suit and carrying a small travel bag in one hand and his smartphone in another. “Have you seen a bridge?” he asked us.

The man and I left the helpless guard and meandered back through the overgrown yards, this time staying alongside the tracks. Not far from there we noticed something in the overgrowth: Two wooden posts that resembled the start of a small footbridge, but they were criss-crossed with slats of wood and there was nothing beyond them. The bridge was gone.

We continued walking back towards the expressway, planning to take the long way around. At some point I considered climbing the fence, climbing down the wooded side of the ditch, over the tracks, and up the other side. That would mean leaving my companion, however, so I scrapped that idea.

Our wandering came to an end when a footbridge appeared before us. It was a newer and better replacement for the old bridge, but why it wasn’t built in the same place as the old one I couldn’t answer, and neither could Google Maps.

Past the tracks it was an easy trek through more alleys and uneven parking lots until I spotted the building number I needed. I pointed my companion—who was in town for work-related training—in the direction he needed to go, full of confidence once again, and wished him vsevó horóshovo (all the best).

The building, a concrete monstrosity that can be found all over Russia, seemed an odd place for a hostel, but on second thought it wasn’t surprising that a Russian would be tempted to turn their apartment into a guesthouse to earn money. The average Russian earns 42,000 rubles per month before taxes, equivalent to around $600.

Soviet apartment buildings don’t have lobbies; instead, they have multiple entrances from the outside for direct access to a stairwell or elevator. This building had four such entrances, and I walked up to all of them in search of a hostel sign. There wasn’t one. I called on the intercom and by phone, but nobody was up that early.

Twenty-something minutes later I got a call back from the hostel owner. After a few rounds of misunderstandings and clarifications—nobody expects a hostel guest to speak Russian, so their first thought is that I’m a confused or scheming local—the owner directed me to another hostel she owns that has available beds at this hour. It wasn’t far… Just over the train tracks.

The Soviet apartment building with a hostel somewhere inside.

The Soviet apartment building with a hostel somewhere inside.

Finding my way past overgrown playgrounds.

Finding my way past overgrown playgrounds.

The new bridge.

The new bridge.

One of the building entrances, with no signs of a hostel inside.

One of the building entrances, with no signs of a hostel inside.

Soviet Devil

After settling in, catching a quick nap, and pushing through some pull-ups at an outdoor gym, I went to church.

The Church on the Blood is the reason I stopped in Yekaterinburg. As the site where Russia’s last emperor, Tsar Nicholas II, was executed along with his entire family in 1918 by Bolshevik revolutionists, it seemed like an important site that must be seen to grasp the tumultuous history of Russia.

It was, therefore, unfortunate that I wore shorts that day. An entrance sign insisted that a mass-execution site is no place for exposed calves: “No shorts.”

The neighboring gift-shop and prayer room did not have a dress code. Also, to my relief, there were outdoor signs explaining the history of the site. I learned that the original house where the royal family was kept and eventually executed was razed by the Soviet government in 1977. Since then, to nobody’s relief, Nicholas II was granted sainthood in 1981, and the church was built a mere 20 years and one collapse of a socialist republic later.

Church on the Blood in Yekaterinburg.

Church on the Blood in Yekaterinburg.

Next door to the church is a small building with a gift shop and a prayer room.

Next door to the church is a small building with a gift shop and a prayer room.

Next, I stopped into a cafe-and-pizza place for lunch and coffee, where I asked a server what there was to do at night. She was new to the city herself, she explained, but usually she and her friends go out to the bars on Ulitsa Vaynera (Vayner Street). “Can I join tonight?” I asked. “But it’s Monday,” she said. I thought about that for a moment with consternation. “I know,” I said. We exchanged numbers and I went on to explore Yekaterinburg.

You couldn’t fault me for thinking it was the weekend; the photography and literary museums were both closed, and the riverfront promenade was buzzing with people. Unlike St Petersburg and Moscow with their masses of tourists, downtown Yekaterinburg had an easy-going and charming feel with just the right amount of people milling about—teenagers, men playing chess, women with strollers, and couples of all ages.

The Iset River in the center of Yekaterinburg.

The Iset River in the center of Yekaterinburg.

The river goes through a small dam and into a man-made pond.

The river goes through a small dam and into a man-made pond.

Posing in front of a “Russia 2018” sign that was put up for the World Cup.

Posing in front of a “Russia 2018” sign that was put up for the World Cup.

A nearby art fair presented a prime opportunity to use up time. As I roamed between stalls of handiwork, art, and various kitsch, a table with hundreds of cast-iron figurines—busts of Lenin and Stalin, laughing devils, ashtrays, and more—came into view. These were popular in the Soviet Union in the 70’s and 80’s. Indeed, I remember two such devils dueling for attention on my parents’ work desk in Moldova (a former republic of the USSR).

The Soviet devil.

The Soviet devil.

I considered buying this replica of a childhood memory, but seeing the mound of figurines strewn out on a table like potatoes at a food market sacked my perceived value of this thing, and I passed. Later, finding them for sale in the US at a 500-percent markup quickly restored my adoration of these little creatures and made me wish I bought the whole lot, but by then it was too late, and I was left once again with only the memory of the taunting Soviet devils.

The Texan

Dinner was at a restaurant-bar a few kilometers from the city center. The large table where I was seated looked sad with just me for company, especially surrounded by other tables filled to capacity. My solution to this awkward situation was to order enough food and drinks to cover the table, and to fill the time between servings by writing busily in my journal. This only attracted the curiosity of an inebriated taxi driver at the next table, but a careful and patient explanation of why I was journaling settled the scene.

Back at the hostel, I met Matthew from Texas. He was traveling on his own, didn’t speak a word of Russian, and was ready to party. I contemplated whether to let him in on my plans with Nastia and her friends… Though I like to keep a distance from Americans abroad, I saw something familiar in Matthew: Here was a fellow solo traveler, deep in Russian territory, except he didn’t know a word of Russian, yet he was still beaming with enthusiasm. “You’re in luck,” I said.

Moments later we were in a Yandex Taxi (the Uber of Russia) flying to some cocktail bar tucked behind a theater. Upon arrival I was disappointed to see the bar nearly empty, save for a small group of people sitting by the entrance. One of them, a bearded Russian hulk, stood and greeted us with an alarming intensity. I mistook him for a bouncer, and became confused when instead of asking for IDs he continued to talk with too much energy for the occasion.

When he learned from my translation that Matthew is from Texas, he simply burst. “Texas?! Tell him…” he said to me in Russian, “tell him I love Texas… I have a cowboy hat… wait here!” I realized this man was not a bouncer, nor a conman, nor a threat of any kind. He was a normal guy; a film instructor, having an after-work drink with his friends, who can’t believe his luck in meeting a Texan in the middle of Russia with a translator at his side.

When the film instructor returned minutes later wearing his cowboy hat, there were already drinks in front of us, everybody was introduced—another film instructor, a movie director, a contortionist, a hairstylist, the bar owner—cameras were flashing, and I was participating in four conversations at once, taking questions from all sides and translating for Matthew so he could, too.

Matthew from Texas (second from right) was an instant hit among a group of locals, especially the Texas-loving film instructor (center).

Matthew from Texas (second from right) was an instant hit among a group of locals, especially the Texas-loving film instructor (center).

As the bar closed at midnight it was time for us to move on. The girls of the group went home, but the film crew, eager to stretch their time with the misplaced Americans, led us to another bar some blocks away.

The night was off to a great start, but it was missing a key ingredient: dancing. Despite warming up to the guys, I didn’t see myself dancing with them. It was time to see what Nastia and friends were up to.

American Girl

I left Matthew with the film crew and walked in the refreshing midnight drizzle to another hidden cocktail bar where Nastia and her three friends made up the entirety of the crowd. After a round of introductions and explaining how I knew Nastia (“We met twelve hours ago—I had coffee”), everyone settled into drinks and tales, and I felt myself among friends.

Nastia is a university student who moved to Yekaterinburg only months ago from some nearby village to study dance. The rigidity of school clashed with her independent personality and she flirted with ideas of dropping out. Nastia’s best friend and the friend’s sister, Arina, were there, though I failed to note any details about them. Another friend, Kiril, spoke fluent English but with an interesting Russian accent. It wasn’t the accent of a Russian person who learned English, but something else… I soon learned he was born in the US and moved to Russia (with his Russian mother) at age 15.

Kiril’s accent was nothing like that of Russian immigrants in New York or the Russian villains of Hollywood. It was like listening to an out-of-practice professional pianist at a school talent show; you’re amazed by their abilities even as you notice they’re off the mark, and you wonder what they’re doing there. I then understood Russians’ reactions when they hear me speak.

Some time later we deliberated on our next move. I petitioned for dancing, but was informed there’s only one dance club open on a Monday night, and it’s a favorite of rowdy and short-tempered students. Before I could get a clear understanding of the average size and strength of a Yekaterinburgian student, a tip came in from Kiril’s friend, Sasha: There’s action at a bar down the street.

Amerikanka (American Girl) is a bar at the end of Ulitsa Vaynera that had open walls facing the pedestrian street, allowing those outside to participate in the party. The crowd was made up of locals, Mexican soccer fans, and one American. And participate they did, as the crowd-aware DJ played a mix of Latin (Dura), Russian (Vokrug Shum), and American (Ride Wit Me) hits.

Outside the bar Amerikanka.

Outside the bar Amerikanka.

Inside the bar Amerikanka.

Inside the bar Amerikanka.

We spent the next four-to-five hours dancing and conversing over speakers and beer—first outside and then inside, after Kiril’s friend and employee of the bar gave us entry.

The exact events are a haze but I can recall being witness to the following: A love triangle emerged between Sasha, Kiril, and Arina; Sasha learned to dance, perhaps motivated to make Arina jealous; another couple appeared, friends of Sasha; Russian women and Mexican men got along quite well; Nastia and her friend left; the price of beer plummeted; and 90’s and 00’s hip-hop made a comeback in Siberia.

The daylight sun—along with the indelicate removal of a straggling dancer by a pair of bouncers—told us it’s time. We stepped out into Tuesday morning, and after smalltalk through squinted eyes I said goodbye to my festive friends.

Me with Kiril, Sasha, and Arina.

Me with Kiril, Sasha, and Arina.

Me, Sasha, and two of Sasha’s friends.

Me, Sasha, and two of Sasha’s friends.

On the walk back to the hostel, I stopped to admire the Iset River, deserted for the moment. It stood still as glass, mirroring its city, unaware and unbothered by shenanigans of restless Russians and a passerby American.

The Yekaterinburg skyline in the serene morning hours.

The Yekaterinburg skyline in the serene morning hours.

Previous chapter: Moscow

Next chapter: The Seal Show in Irkutsk