Journey on the Trans-Siberian: The Seal Show of Irkutsk

This is part of a series about my journey across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railway, from St Petersburg to Vladivostok, in the summer of 2018. This part covers my two nights in Irkutsk, in the heart of Siberia.

Location of Irkutsk, deep in Siberia.

Location of Irkutsk, deep in Siberia.

Welcome to Irkutsk

Following a successful outing in Yekaterinburg almost a week before, I was ready to repeat it in Irkutsk.

After Dasha, the hostel manager, gave the usual hostel welcome of pointing out the bathroom and marking our location on a map, I asked about bars where people dance. Dasha wasn’t sure what to make of this request. “Dance to what?” she said. “Whatever people listen to these days… like Kasta,” I said, recalling a rap group whose song played in Yekaterinburg to wild fanfare. “Kasta?” she said, “People listened to them in the 90’s.”

She pointed to a nearby row of bars and restaurants and wished me luck.

The evening streets of Irkutsk are dark and empty, with just a few street lights on each block, supplemented by infrequent passing headlights and even more rare chatter of passing pedestrians.

Empty evening streets of Irkutsk.

Empty evening streets of Irkutsk.

A Belgian bar offered shelter, light, ambient sound, and distraction with the projection of a World Cup game, playing out in the same country five time zones away.

After the game I stepped into the cocktail lounge next door in search for any music and excuse to dance. The place was small and upscale, with patrons looking too-cool-to-dance and dressed much nicer than me. I lost the motivation.

The Seal Show

In the morning I ventured out to see what day-time Irkutsk has to offer.

Even fewer people, it turns out. A group could be found coming out of an historic church in the city center, shooing away homeless beggars. Some handful of men in outdated military uniforms were preparing to celebrate something nearby, where an eternal flame for fallen soldiers—there is one in every Russian city—occupied the center of a large public square.

Eternal flame in the center of Irkutsk.

Eternal flame in the center of Irkutsk.

Public square and few signs of life.

Public square and few signs of life.

Across the public square and wide thoroughfare—both of which seemed three times too large for the city’s population—is the riverside promenade.

This promenade, according to Russians on the Yekaterinburg-Irkutsk train, should be bustling with families and buskers and strolling seniors. This Sunday morning it was empty and silent for its entire visible stretch. The other side, across the Angara River, seemed equally uneventful with its shrubby fields and industrial structures.

Promenade alongside the Angara River.

Promenade alongside the Angara River.

The sun was getting stronger and it was time to try something else.

I first learned about the nerpa (Baikal Seals) in a book about traveling in Siberia. This species of seals can only be found in Lake Baikal, whose closest shore is just 70 km from here. The same book mentioned an aquarium in Irkutsk where the nerpa can be seen; a convenience for those who couldn’t make the trip to Lake Baikal or, like me, experienced foggy weather when they did.

A Yandex Taxi (like Uber for Russia) pulled up as ordered, and off we went to the Irkutsk Nerpinary.

We crossed Angara River to the west bank of Irkutsk. Instead of soviet-era boulevards, monuments, and government buildings in central Irkutsk, the west bank was more residential, with two-lane roads sparsely lined with three-to-six story apartment buildings, barber shops, and gas stations.

It made sense that an aquarium would be in the city outskirts, where there’s plenty of space for pools, auditoriums, parking lots, and loading docks to receive fish by the ton. It did not make sense that the Yandex Taxi app showed we were already approaching the destination despite still driving through the residential area.

As I swivelled my head to look for a large aquarium structure, a wooden sign caught my eye. At the entrance of a three-story brick home, below a “for rent” banner, was a cartoonish seal either smiling or rolling its eyes. It was perched on the words “Nerpa Aquarium: Nerpinary.”

Even the local driver did not expect it to be there, and drove another 50 meters before realizing he passed the destination pin. “Did we pass it?” he said. “Yes, I think I saw it,” I said, still not convinced myself.

Past the entry gate with its mocking seal, visitors step down from street level and towards the home’s basement entrance where the echoes of seals barking and the smell of chlorine greet them as if to say “Yes, yes, this is the place. Hah! Surprised? Bark bark bark.”

The nerpa aquarium in Irkutsk, housed in a residential brick home.

The nerpa aquarium in Irkutsk, housed in a residential brick home.

The main entrance opens to a small waiting room—or living room—with several chairs lining three walls and an enclosed ticket counter by the fourth. Behind the ticket counter was a stout russian woman with dyed blond hair, and behind her an array of plush nerpas. Photos of the seals hung on the walls, some with small children shown kneeling by their side.

Opposite the ticket booth was a door on which a sign said shows start every 30 minutes, warned not to enter, and prohibited photographs. Behind the door, evidenced by the barks of seals, commands of the microphoned trainer, splashes of water, and occasional clapping emanating from it, a show was in progress.

Inside the nerpa aquarium.

Inside the nerpa aquarium.

Two parents and their two preschool daughters were already seated in the chairs and waiting for the next show. If they or the ticket-counter lady wondered why a 30-year-old man walked into the waiting room of an aquatic children’s petting zoo, they hid it well.

“I’m already here and have nothing else to do,” I thought, stepping to the ticket counter with 350 rubles ($5) in hand. “One adult, please.”

Several more people strolled in as we waited for the show, always with small children or grandchildren. The kids begged for plush toys and parents pointed at cute nerpa photos on the walls to distract them. I considered leaving more than once.

If the book included this place then it means the author was here, too. Therefore, even if it is strange for a grown man to watch a kids’ seal show in the basement of an Irkutsk home, at least I wouldn’t be the first. Besides, it would make for a good story. I leaned back and lifted my chin in a show of commitment.

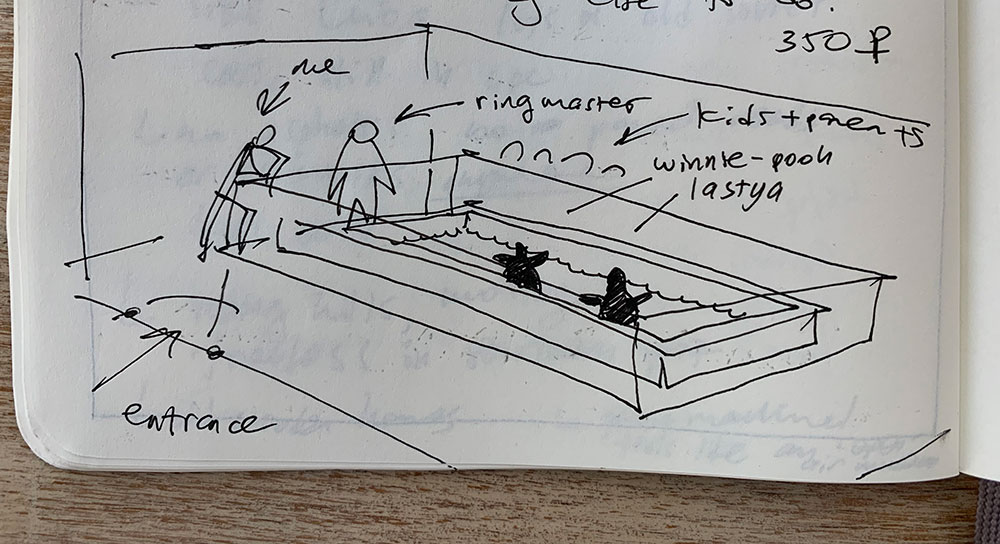

Right on schedule the door opened and we filed through into a tiled room, about 15 feet wide and 50 feet long, with a long and narrow pool in the middle, surrounded by metal railing.

Without missing a beat the ringmaster rattled into her wireless microphone and introduced Lastya and Winnie-Pooh as they entered the pool through an underwater tunnel. The audience greeted them with an applause and they responded in kind.

Sketch of the pool inside the nerpa aquarium.

Sketch of the pool inside the nerpa aquarium.

Over the sounds of applause, splashing water, and amplified Russian the seals performed a series of tricks as directed by their ringmaster’s subtle hand gestures. They jumped, danced, rotated like ballerinas, slapped their bellies, gifted flowers, kissed, played basketball and soccer, surfed, and even played instruments—Lastya on the sax and Winnie-Pooh on the trumpets—pausing between each act for a fishy treat.

In my favorite display of nerpa talent, the trainer placed a large piece of paper by the pool’s edge, dipped a brush into blue paint, placed the brush into Lastya’s mouth, and motioned for her to jump and smear some paint onto the paper. They repeated this with red, yellow, and green paint, finishing with a dab in the bottom-right corner to sign the work of art.

The audience—including yours truly—gave a round of applause. Continuing with the script, the trainer announced the abstract painting will now be auctioned to the highest bidder. “Who will be the lucky person to bring home this unique work of art? We will start with 150 rubles,” she said ($2.30). A loving mother raised her hand. “Now 200, 200, 200, who wants to take this priceless nerpa masterpiece home, for 200, ladies and gentlemen!” A girl of around eight whispered something to her dad, who then raised his hand to bid 200 rubles ($3.10).

Meanwhile I was calculating the following:

- There’s worse art sold at Brooklyn flea markets for 50 times this price.

- I can bid the price of a Brooklyn brunch and blow the competition out of the water.

- This would be a fun story to tell when visitors notice the framed scribbles in my home. “Did your nephew paint this,” they might ask. “Actually…”

By the time I decided against depriving one of the present children of this souvenir, the auction concluded at 300 rubles ($4.60) and the painting was rolled up and handed to the winner and their delighted kids. I still got my story.

(You must think I hallucinated this seal performance, perhaps from heat stroke or from inhaling too much chlorine. How convenient, you might think, that photos and videos weren’t allowed there… Well then, see for yourself.)

Plywood Monument

The area around the… aquarium… Included a flea and food market, a small shopping center, a kvass stall (fermented drink made from black bread), but not a barbershop, which I confirmed by strolling through all of the above.

I returned to central Irkutsk, this time to the tourist district, replete with bars, bad restaurants, a trendy coffee shop, expensive gift shops, and, to my delight, a barbershop that could, after some convincing in strained Russian, give me a lineup.

Tourist area of Irkutsk, with shops and restaurants.

Tourist area of Irkutsk, with shops and restaurants.

A fresh haircut deserves fresh air, so I made my way towards the Central Park of Culture and Rest. The park was once a cemetery and then an attraction park, before turning into grassy trails and sporadic trees. It could use a lineup, too.

The park was empty, except the occasional biker, young couple, or passerby resting behind and under the bushes, as surprised to see me as I was to see them. The park’s only sight, a monument to war heroes, was covered in plywood “for restoration.”

Central Park of Irkutsk.

Central Park of Irkutsk.

Monument to the war heroes.

Monument to the war heroes.

After the park I walked down quiet streets of old Irkutsk, with single-level wooden homes on either side, their visible leans showing their state of disrepair. Peeks into the askew homes revealed furnished kitchens, cats, and other signs of habitation. Fitting structures for a city that housed exiled Russians in the early 20th century.

Aging wooden home.

Aging wooden home.

Overgrown sidewalk in Irkutsk’s old center.

Overgrown sidewalk in Irkutsk’s old center.

Another dilapidated home in the center of Irkutsk.

Another dilapidated home in the center of Irkutsk.

Slanting wooden homes.

Slanting wooden homes.

Shootouts at Star Bars

Back at the hostel I took care of errands (food for the next leg of the train trip, laundry) and called my wife (12 hours’ difference). I consulted with the hostel manager (another Dasha) where to watch that night’s World Cup quarterfinal match, featuring, for the first time in 48 years, Russia.

Every table at Star Bars, the Star Wars-themed bar recommended by Dasha, was reserved days in advance for this match. Bar seating, however, was first come first served, and I came two hours early.

The two hours passed by as I ate plate after plate of bar food, sipped on cocktails, and explained to the bartender not for the first time what I was doing there and why my Russian sounds strange.

Ready for the World Cup game in Star Bars.

Ready for the World Cup game in Star Bars.

Hours later, the match between Russia and Spain ended in dramatic fashion with penalty shootouts, from which Russia emerged victorious. Star Bars erupted. “We Are the Champions” by Queen blasted through the speakers as the crowd sang along in broken English, then the Russian party anthem “Rayoni Kvartali” by Zveri came on and I sang along in broken Russian:

Nothing left for me to snatch, I caught everything I need

Before they get used to it, it is time for me to leave

Sunglasses in bright yellow, two red hearts on my key band

Razzled pupils in my eyes, your name written on my hand

Districts, neighborhoods, overpopulated blocks

I am leaving, leaving looking good

Districts, neighborhoods, overpopulated blocks

I am leaving, leaving looking good

(Roughly translated.)

Mafia

A third Dasha was on duty at the hostel when I returned from Star Bars. It was her first night on the job, and she invited her friends to keep her company. I stayed up with them so they could keep me company, too.

The hostel is inside a typical wooden home in the old center of Irkutsk.

The hostel is inside a typical wooden home in the old center of Irkutsk.

We sat around an oval table in the living room and spoke with fascination about their lives, mine, and their future. They were all university students and spoke english in varying degrees.

There was Ilya the law student, Alina the heartbroken, Anya the future translator, Misha the English novice, Nastya the opera student, Jesus of Spain who spoke neither English nor Russian and came to Irkutsk to meet his fiancee’s family, Lera who studied abroad and will mary Jesus, and Dasha the hostel employee of the day. This was the atmosphere I failed to find on my first night in Irkutsk, and I was soaking in every hour.

Well after midnight we started a game of mafia, in which the game host secretly appoints someone as the hitman, and the group must figure out who it is before they’re all killed. At frequent intervals Dasha had to remind the mafia to quiet down; there were people sleeping.

From left: Dasha, Misha, Anya, Alina, Ilya, me, Lera, Jesus, and Nastya.

From left: Dasha, Misha, Anya, Alina, Ilya, me, Lera, Jesus, and Nastya.

Tomorrow morning I would catch the train once again onward to Vladivostok. Three days on the rails, with to-be-determined cabin-mates and personalities.

But that’s hours away. Right now I am distracted with friends and their stories, and the hunt for the Hitman of Hostel 52-17.